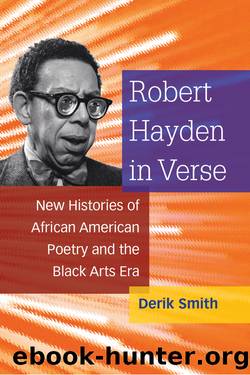

Robert Hayden in Verse by Derik Smith

Author:Derik Smith [Smith, Derik]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: University of Michigan Press

Here guilt,

here agenbite

and victimizer victimized by truth

he dares not comprehend.

Here the past, adored and unforgiven,

its wrongs, denials, grievous loyalties

alive in hard averted eyesâ

the very structure of the bones: soul-scape

terrain

of warring ghosts whose guns are real.

Haydenâs haunted southern landscapes of the 1950s are dangerous and violent, âhard bitten and sore-beset.â They flower âwith every blossom fanged and deadly.â They are sharp, serrated by alliteration: âthe landscape lush, / metallic, flayed; its brightness harsh as bloodstained swords.â And thus they are another rejoinder against the fantasy imagery of plantation literature suggested in Stephen Benétâs hope for a black-skinned poetics harmonized in the âSoft mellow of the levee roustabouts, / Singing at night against the banjo-moonââ (348). Haydenâs southern landscapes, imbuing natural ecology with a history of violence, participate in a tradition that Ãdouard Glissant finds throughout the postcolonial writing world. While planter and colonial classes of European stock willed into being the sensuous literary charm of the plantation landscape (Benétâs âbanjo-moonâ in the soft night), ethnic writers of the twentieth-century Atlantic world stamped that same space with the viciousness that gave life to colonial society. As Glissant puts it, the colonial world developed an aesthetic emphasizing âthe gentleness and beautyâ of the landscape, meant to âblot out the shudders of life, that is, the turbulent realities of the Plantation, beneath the conventional splendor of sceneryâ (70). The response was an ethnic literature that âwent against the convention of a falsely legitimizing landscape and conceived of landscape as basically implicated in a story, in which it too was a vivid characterâ (71).

Haydenâs âbloodstainedâ southern landscapes are then in keeping with a resistive paradigm of representation that Glissant thinks of as âcreative marronage.â Likening cultural dissent to the political insurgency of the Maroons (slaves who escaped into the hills of the Caribbean islands to form fugitive communities in opposition to plantation order), Glissant identifies several forms of representational disruption in the work of New World writers. Violent vivification of landscape is only one strategy of interference he recognizes. More central to creative marronage is the deformation of a traditional linear concept of time so at odds with a New World reality marked by the continual explosion of linguistic, familial, and ethnic continuities. Within the reality that Glissant metaphorically spatializes as the âPlantation,â âthe always multilingual and frequently multiracial tangle created inextricable knots within the web of filiations, thereby breaking the clear linear order to which Western thought had imparted such brillianceâ (71). Haydenâs 1950s poems, stabbing fragments of the past into landscapes of the writing present, cutting through tidy temporal boundaries, seem to be quintessential examples of the creative marronage undertaken by New World writers who responded to âPlantationâ history by exploring the âcoils of timeâ and asserting that, to quote Glissant once again, âMemory in our works is not a calendar memory; our experience of time does not keep company with the rhythms of month and year aloneâ (72).

Yet, as Iâve argued, the temporal manipulation and deformation of Haydenâs poetry of the late

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12405)

The handmaid's tale by Margaret Atwood(7773)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(7354)

Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear by Elizabeth Gilbert(5780)

Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne & Stuart M. Keeley(5779)

Ego Is the Enemy by Ryan Holiday(5456)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(5104)

On Writing A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King(4948)

Ken Follett - World without end by Ken Follett(4740)

Adulting by Kelly Williams Brown(4582)

Bluets by Maggie Nelson(4566)

Eat That Frog! by Brian Tracy(4547)

Guilty Pleasures by Laurell K Hamilton(4455)

The Poetry of Pablo Neruda by Pablo Neruda(4113)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(4037)

White Noise - A Novel by Don DeLillo(4019)

Fingerprints of the Gods by Graham Hancock(4009)

The Book of Joy by Dalai Lama(3996)

The Bookshop by Penelope Fitzgerald(3857)